Join us on Facebook!

Join us on Facebook!

— Written by Triangles on September 10, 2021 • updated on November 17, 2021 • ID 93 —

A theoretical look at one of the most popular programming tools for exchanging data over computer networks.

Introduction to computer networks — A bird's-eye view on the art of resource sharing from one computer to another.

Understanding the Internet — “Is that thing still around?” — Homer Simpson

Introduction to the TCP/IP protocol — The official rules that allow computers to communicate over the Internet.

Introduction to IP: the Internet Protocol — From routing to IP addressing, a look at the protocol that gives life to the Internet.

Introduction to TCP: Transmission Control Protocol — One of the most important, high-level protocols in the Internet Protocol Suite.

Making HTTP requests with sockets in Python — A practical introduction to network programming, from socket configuration to network buffers and HTTP connection modes.

Welcome to the 6th episode of the Networking 101 series! I've spent the last five chapters talking about the theory behind computer networks, from the Internet history to some of the most important Internet protocols out there. Now it's time for me to explore one of the many practical sides of networking: network programming.

Network programming is about writing computer programs that talk to eachother over a computer network. The world is full of such type of programs: for example, the web browser you are using to read this website is a piece of software that connects to a remote computer where the data is stored and grabs the text content to display on your screen.

The browser and the web server can do their networking job thanks to the operating systems they run on, where all the necessary network protocols have been implemented. The operating system's parts that provide network functionality are called sockets.

A socket is an abstraction over a communication flow. Concretely, sockets are programming objects provided by the operating system that allow your programs to send and receive data. There are two types of sockets in the programming world:

network sockets — they are used to exchange data between programs over a network, or in other words between two remote hosts;

Unix Domain sockets — also known as UNIX sockets, they are used to exchange data between programs running on the same machine (i.e. in the same host). This is a form of Inter-Process Communication (IPC).

This article is about network programming, so I will focus only on the first type. However, sockets in modern operating systems support both styles: changing the socket type is just a matter of configuration, as we will see shortly.

A socket is an object that you create, configure and on which invoke some functions to send or receive data. For example, the pseudo-code below shows how to send a piece of text (Hi there) through a fictional socket:

Socket socket(...configuration...) (1)

socket.connect(...address of a remote host...) (2)

socket.send("Hi there") (3)

socket.close()

A socket is first created and configured (1), then it is used to establish a connection to a remote host (2) and to send the message (3). Sockets are the foundation to more complex programs that send and receive data: we will see some examples of what you can do with them in the last part of this article.

The example above is just pseudo-code: actual sockets come with the operating system, so they are written in low-level languages (C, mostly). Their programming interface (API) however — the socket object layout, how to initialize it, the function names, ... — is very similar to the pseudo-code above. In fact, such API style is known as the Berkeley sockets interface, sometimes also called POSIX sockets or BSD sockets.

All modern operating systems implement the Berkeley socket interface, but not all of them stick to the original specifications. Also, using sockets provided by the operating system forces you to write low-level code. That's why most of the time you want to use the networking abstractions provided by higher-level programming languages. For example, the std::net module in Rust, the jdk.net package in Java or the Boost.Asio library for C++.

Python is interesting: its socket module is the translation of the Berkeley sockets interface into Python's object-oriented style. The advantage is that you work with the original API without all the headaches of manual memory management required by the C language. For this reason I will be using Python and the socket module for my network programming experiments in the next chapters of this series.

As mentioned earlier, a socket must be configured before use. You have to specify the socket family, the socket type and the optional protocol. Those properties define the nature of the socket and its behavior. Let's take a deeper look.

Determines whether you want a socket that works over the Internet or a local one. More specifically, you can have IPv4-based sockets, IPv6-based sockets or UNIX sockets.

A socket configured as IPv4 or IPv6 can exchange data with remote hosts. The former works with IP addresses version 4, the latter works with IP addresses version 6. A socket configured as UNIX is used to exchange data between programs on the same machine. Windows, a non-UNIX operating system, recently added support for the UNIX socket type.

Determines the type of communication you want to establish. Here the choice boils down to three types: stream sockets for connection-oriented protocols such as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP); datagram sockets for connectionless protocols such as the User Datagram Protocol; raw sockets for low-level communication protocols such as the Internet Protocol.

With stream or datagram sockets you are using popular protocols already implemented for you by the operating system. Raw sockets instead allow to do whatever you want: you can implement your own protocols, generate custom IP packets, intercept network traffic or just mess around by sending invalid data to other computers.

Raw sockets are powerful and might cause harm if used for malicious purposes. This is probably the reason why raw sockets on Windows are in read-only mode: you can't send data with them.

This piece of information is often optional, as sockets can automatically determine how to behave given the family and the type described above. For example a stream, IPv6-based socket is automatically prepared for a TCP-over-IPv6 transmission. Even better, the Berkeley sockets API includes some utility functions to determine the right parameters for the socket configuration given the address you want to connect to.

As a designer, you can do whatever you want with sockets. However, socket-based programs usually end up being clients or servers. Clients establish the connection to servers, which in turn listen to clients and exchange data with them.

For example, the browser you are using to read this article is a client: it talks to a remote server that contains the web page to be displayed. Both the browser and the server make use of sockets under the hood for the actual data transmission.

The pseudo-code snippet I've shown you before is a client. Let me put it back here for clarity:

Socket socket(...configuration...)

socket.connect(...address of a remote host...)

socket.send("Hi there")

socket.close()

A server is different in that usually it waits for new clients coming in. Here's a pseudo-code example of a server that replies back to clients with the Welcome string:

Socket socket(...configuration...)

socket.bind(...address...) (1)

socket.listen() (2)

while (...some condition...):

client = socket.accept() (3)

client.send("Welcome")

socket.close()

Beyond the usual configuration, the Berkeley sockets API wants to bind the socket object to an address (1). This means that your program will react when it receives data from a client with a certain IP address, for example.

What you can define in the ...address... part actually varies between the protocol in use. For example in a TCP connection you also have to specify the port a client can connect to, and if you don't pass any IP address in it your server will accept connections from any client.

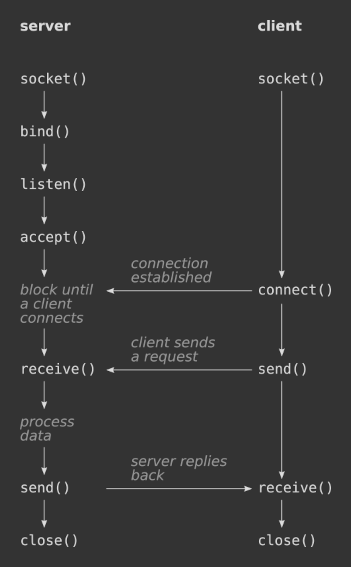

The socket is then instructed to listen (2), to make it accept incoming connection requests from clients. Finally, the program waits for new clients to come in with the accept() function (3). From this point on, the server has established a connection with a client and can send data to it. The picture below shows the API calls involved in a typical scenario of a client and a server talking to eachother.

The accept() function in the server pseudo-code above is blocking: the while loop doesn't make any progress until a new client arrives. In other words: your program is stuck waiting for new connections.

The same logic applies to the connect() function in the client example: no progress is made until a connection is established. Sockets are blocking by default, but you can put them into non-blocking mode during the configuration stage.

With non-blocking sockets the functions mentioned above return immediately without waiting. This is especially useful for servers that need to handle thousands of connections at the same time, or more generally when you want to write programs that don't get stuck waiting for external events.

Non-blocking programs are faster, but your code becomes a little bit more complicated as you are entering the realm of asynchronous programming. Choosing blocking versus non-blocking mode is usually a trade-off between performance and programming complexity.

When communicating across a network, you may encounter computers with a different architecture than yours. Byte ordering is what changes the most: how data is stored in memory.

Take the hexadecimal number 0xA4FFBC01 for example: some computers store the most significant byte (A4) before the less significant byte (01), so that the number in memory appears as it is written (A4 FF BC 01). This way of storing numbers matches how us humans write things down and is called big endian. The standard byte ordering in networking is big endian and for this reason it is also known as network byte order.

Some computers do the opposite instead: they store the most significant byte (A4) after the less significant byte (01), so that the number in memory appears flipped (01 BC FF A4). This byte ordering is called little endian, known as host byte order in the networking jargon.

So, exchanging data between two computers with different byte ordering requires an adjustment. The trick is to convert data to network byte order before sending it, and convert it to host byte order on arrival. This is done through some utility functions that come with the Berkeley sockets API such as the hton* and ntoh* families: they read as host-to-network and network-to-host and perform the byte conversion for you.

This article wanted to be a lightweight overview of the Berkeley sockets API. In the next one I will write a small client that downloads a web page from a web server. The experiment will help us understand how to set up a socket, how the send/receive mechanism works and many other nuances of TCP, the protocol the web is based on.

Wikipedia — Network socket

Wikipedia — Unix domain socket

Wikipedia — Computer network programming

Wikipedia — Berkeley sockets

StackOverflow — Unix vs BSD vs TCP vs Internet sockets?

Microsoft — TCP/IP Raw Sockets

Microsoft — Porting Socket Applications to Winsock

Socket Programming in Python

Python manual — socket: Low-level networking interface

Beej's Guide to Network Programming