Join us on Facebook!

Join us on Facebook!

— Written by Triangles on August 03, 2021 • updated on September 09, 2021 • ID 91 —

One of the most important, high-level protocols in the Internet Protocol Suite.

Introduction to computer networks — A bird's-eye view on the art of resource sharing from one computer to another.

Understanding the Internet — “Is that thing still around?” — Homer Simpson

Introduction to the TCP/IP protocol — The official rules that allow computers to communicate over the Internet.

Introduction to IP: the Internet Protocol — From routing to IP addressing, a look at the protocol that gives life to the Internet.

Network programming for beginners: introduction to sockets — A theoretical look at one of the most popular programming tools for exchanging data over computer networks.

Making HTTP requests with sockets in Python — A practical introduction to network programming, from socket configuration to network buffers and HTTP connection modes.

Welcome to the 5th episode of the Networking 101 series! In the previous chapter I talked about the Internet Protocol, a fundamental piece in the Internet Protocol Suite that gives life to the Internet as we know it. The Internet Protocol introduces important concepts such as routing and IP addresses that allow two or more computers located on different networks to exchange data.

As seen in the previous episode, communicating through the Internet Protocol is straightforward: split your message into small chunks of data (datagrams) and send them to the recipient's computer (host) connected to a network. Routers will do the job of delivering your datagrams to the correct destination by passing them around until the target host is reached. The Internet Protocol works like the postal service: you write the address on the letter, post it and hope it will safely reach the destination.

This way of exchanging data is essential for the Internet to work correctly, but it's too limited for a practical communication: will the recipient receive the data? What if it gets corrupted or lost along the way? In case of multiple datagrams, how to make sure they are received in the correct order? The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) exists to answer all those questions — and much more.

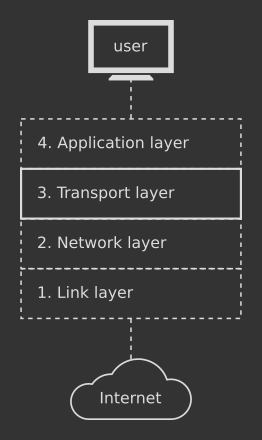

The Transmission Control Protocol belongs to the Transport layer (#3) in the Internet Protocol Suite and it's one of the most important protocols in the entire stack. It makes use of the Internet Protocol as a foundation and adds many features on top of it.

TCP has been designed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and you can find the original specification here, along with additional updates (1, 2, 3, 4).

The Transmission Control Protocol introduces several improvements over the low-level Internet Protocol, both conceptually and technically:

TCP is connection-oriented — a connection must be set up between two or more hosts before exchanging data;

TCP follows the client-server model — a hierarchy is established between two or more hosts that want to communicate. The server provides data to clients;

data transfer is ordered — if you send A, B and then C, TCP guarantees you that the recipient will receive A first, B and then C in that exact order;

lost data is retransmitted — TCP makes sure the entire block of information reaches the target host. If a portion of it is lost, TCP issues a retransmission;

data is validated through error correction mechanisms — data might get corrupted along the way. TCP is capable of detecting and fixing errors;

flow and congestion control — a computer in a slow network might be quickly overwhelmed by another one that sends data from a fast network. TCP has complex strategies to regulate how fast or slow data should be sent between hosts.

TCP is a robust and reliable protocol for exchanging data, but on the other hand it increases the level of complexity if compared to the simpler IP. I will take a look at those intricacies in the last part of this article.

As IP is the foundation of TCP, so several protocols from the upper layers in the Internet Protocol Stack are based on TCP. For example, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is one of the most important protocols for browsing the web. The page you are reading right now has been obtained by your browser thanks to a TCP connection established by HTTP to the web server that stores this website. Two other important TCP-based protocols are the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) — used to transfer files between computers and the Secure Shell Protocol (SSH) — used to connect to another computer in a secure way.

The protocols mentioned above (and many others) need the robustness and reliability provided by TCP in order to work correctly. For example, TCP makes sure that the text you are reading right now is fetched correctly from the HTTP server, in the correct order, without missing pieces or damaged parts.

Like any other protocol, TCP is just a set of rules written on paper: the actual implementation is done by operating systems through special entities called network sockets. A network socket is a programming object that allows two hosts to send and receive data. I will explore network sockets later on in this series when I will get my hands dirty with network programming.

If the Internet Protocol looks like the postal service, using the Transmission Control Protocol is like making a phone call: you need to establish a connection before being able to talk. Concretely, the process is made up of three phases: 1) create a connection between the hosts; 2) transfer the data; 3) close the connection. The key point of a TCP connection is the ability to transmit data in both directions at the same time: from sender to receiver and vice versa. This is known as a full-duplex data transmission.

During a TCP connection, the host that provides data is the server, while hosts that receive it are the clients. For example, this website is stored in a computer connected to a network located somewhere on the Internet. When you ask your browser to navigate this website, the browser itself establishes a TCP connection between your computer and the computer where the website is stored.

Your computer is the client, while the computer containing the website data is the server. The server sends the text content to the client, while at the same time the client sends information to the server about specific instructions such as which page to get, how to transfer data and so on. This is the full-duplex transmission in action.

Since TCP is based on IP, you need to specify the IP address of the server you want to connect to. On top of that, TCP uses special numbers, called ports, to determine the type of service you want from the server. For example, port 80 is used to exchange web pages such as this one; port 23 is for transferring files and so on. A server may be able to offer multiple services, thus having multiple ports available.

A TCP connection is established by following three steps, also known as the three-way handshake. Two hosts that want to connect through TCP must first exchange a set of special messages — SYN, SYN-ACK and ACK — in the correct order. If the negotiation is successful, the connection takes place and the two hosts can start sharing data.

A TCP connection is closed through another negotiation made of four steps called four-way handshake. The host that wants to terminate the connection notifies the other end, which in turn replies back. The connection is closed successfully after the exchange of a set of special messages — FIN and ACK — in the correct order. I will take a closer look at the TCP handshakes and actual TCP communication in the upcoming network programming part of this series.

In the third chapter of this series I mentioned how the Internet Protocol Suite wants the data to be split into chunks: TCP calls those chunks segments. Everything that is send over a TCP connection, from the handshakes described above to the actual data, is contained into a TCP segment. Segments are generated by programs from upper layers in the stack that make use of TCP.

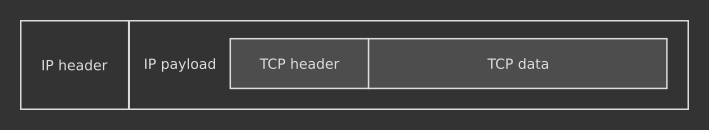

A TCP segment is made of two parts:

The whole TCP segment is then fitted into an IP datagram's body, as seen in the picture above. Since TCP is based on IP, it uses IP datagrams to carry data around the Internet according to the IP routing mechanisms seen in the previous episode.

As I said before, TCP adds lots of improvements over the bare-bone IP: let's take a quick look.

Data transmission at lower levels of the Internet protocol stack is messy: IP datagrams may be delivered out of order. For this reason, each TCP segment has a special field in the header called sequence number. This field contains a number, generated by the sender, that gets incremented every time a new segment is sent. The receiver uses such information to identify the order of the segments received and reconstruct the correct sequence.

IP datagrams may be lost too. The receiver sends a special message (ACK) to the sender to inform it when a segment has been received. If the sender doesn't receive the confirmation message, it interprets it as a segment lost on the receiver side and tries to send it back again.

There are several techniques outlined by TCP to detect losses and retransmit data. For example, a timer called Retransmission Timeout (RTO) is used by the sender to monitor missing confirmations by the receiver. If the receiver doesn't send the special ACK within a certain time frame, the sender resends the segment. A more advanced trick known as Fast-Retransmit is based on duplicate ACK messages sent back by the receiver when a missing datagram is detected.

Each TCP segment contains in the header the Checksum field, a special number used to determine if the packet is valid or corrupted. The checksum is calculated by the sender using a specific algorithm, then stored in the header and sent to the receiver. The receiver computes the checksum on the received segment using the same algorithm as the sender and compares its value to the checksum passed in the header. If the values do not match, the segment is rejected.

TCP is designed to adapt to hosts and networks with different speeds. TCP's flow control is a mechanism where the receiver tells the sender how much data it is capable to process, so that the sender can adjust its rate accordingly. TCP's flow control is based on the Sliding Window protocol, an algorithm used to keep track of how much data the receiver has got from the sender. When the receiver has its local buffer full of data — the window is full according to the algorithm's jargon —, the sender must wait.

TCP can also prevent network congestion: a situation where a host processes more data that it can handle. When a network is congested, data is delayed or lost and new connections cannot be established. TCP employs several algorithms to prevent that, especially in modern implementations. The core idea is to keep the data flow below a rate that would trigger congestion. This is probably the trickiest part of TCP.

All the good stuff mentioned above makes TCP a very accurate protocol: data will hardly be lost in a TCP connection. However, waiting for out-of-order messages or retransmission of missing pieces may take time. For this reason, TCP adds latency: a time delay between a user action and the resulting response.

High latency is not a big problem with non-real-time applications: you can comfortably wait few milliseconds to fully obtain a web page from a server. On the other hand, TCP is not suitable for things that require a fast response, such as phone/video calls over the Internet or online games. For such applications, User Datagram Protocol (UDP) is usually recommended instead. I will dig into UDP in one of the next episodes of this series.

I've spent the last five chapters exploring the theory behind the modern Internet. It's now time to put in practice what I've learned so far and see how all those protocols work in the real world: enter network programming, the art of writing apps that talk to eachother over a network. See you in the next episode!

Wikipedia — Transmission Control Protocol

Wikipedia — Connection-oriented communication

Wikipedia — TCP congestion control

Wikipedia — Latency (engineering)

Khan Academy — Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

Gaffer On Games — Virtual Connection over UDP

inetdaemon.com — TCP 3-Way Handshake (SYN,SYN-ACK,ACK)

packetlife.net — Understanding TCP Sequence and Acknowledgment Numbers

Javis in action — Fast-Retransmit Algorithm